|

Monday, 20 August 2012

The Rebirth of Maryland Avenue

Saturday, 3 March 2012

More News from Barcelona

Down at the Ajuntament, Barcelona’s planners never sleep. For years now, they’ve been working on hugely ambitious plans to make this the most technologically advanced city in the world. The latest step, unveiled March 1st, is a partnership with Cisco Systems to create something called the ‘Barcelona Institute of Technology for the Habitat’.

The city is committed to building a new campus for it in the heart of it’s rapidly-developing high-tech district ‘22@’ (pronounced vint-i-dos arroba), near Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes and Jean Nouvel's Torre Agbar. ‘BIT for the Habitat’, as they call it, will be a centre for research and education into ways technology can improve city life. For Cisco, it’s enlightened self-interest. They make software and systems, and they want to help cities learn to use them in the same way that GE, Westinghouse and other firms helped wire cities for street lighting over a century ago.

For Barcelona, it’s all part of an umbrella plan called Barcelona Smart City, which hopes to use the latest technology to promote sustainable development and make city services more efficient. Since 2008 they’ve begun 43 pilot projects: redoing the street lighting system with LED technology, installing charging points for electric cars, smart metering for gas, electricity and water, a computerized system to lead drivers to available parking, and more bike lanes on the streets. They have plans to make better use of the rain water that falls on the city, to start a system of electric and solar-powered motorbikes for public use, and to create entire city blocks that are self-sufficient in energy.

Friday, 10 February 2012

And Now the Bastards Want to Wreck My High School

photo: Aaron Turner, oldohioschools.com

photo: Aaron Turner, oldohioschools.com

Sunday, 29 January 2012

A New Center for Barcelona

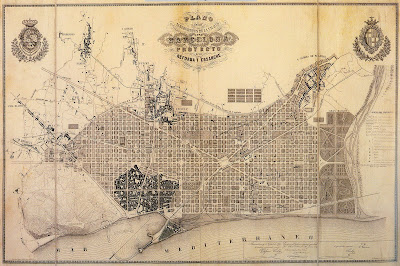

The Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes was conceived in Ildefons Cerdà’s great 1859 plan for the Eixample (‘extension’). That’s it in the center of the plan, below, at the spot where Avinguda Diagonal and the Gran Via meet. Cerdà meant it to be the center of the new Barcelona, but he would be betrayed by shifting patterns of fashion and real estate. The Square of Catalan Glories became a tawdry urban backwater, famous only for changing buses, and for the huge, surreal flea market called Les Encants that still, for the moment, graces its northern side. Eventually, Franco slopped a mess of concrete road junctions around it.

Barcelona resolved to fix up the Glòries in the 80’s. In those days, a city bursting with cash and energy was convinced it had the architectural and artistic talent to match. Barcelona was wrong. Nearly all of its early megaprojects were hideous flops, and none more so than the rebuilding of the Glòries. Here, a demented architect simply rearranged Franco’s auto flyways into a giant traffic circle in the sky, propped on concrete piers that covered most of the square. City Hall was promised that the people would delightedly gather underneath and perhaps open up cafés and dance sardanas; instead it rapidly became a spooky, crime-ridden wasteland. Within a few years of its opening, locals were screaming for its demolition.

Now they’ve got their wish. Photos of this incarnation of the Gloriès can still be found here and there on the web, though one suspects the Barcelona municipality is secretly buying them up to hide the evidence. Now they’re doing it all over again, at a cost of over a billion euros, and this time good, simple planning and a massive revival of investment in the area have coincided for a new Glòries that soon might become one of Europe’s iconic urban spaces.

As Boston learned with its Big Dig, the simplest and best solution was also the most expensive and nerve-wracking: get rid of the cars. Here too, the only way to do that was to swallow them underground, not an easy job in a spot where three major roads meet, and will have to share the underground space with metro, tram and bus stations. On top, we’ll see a huge new park—the size of eight soccer pitches. How such a large open space gets landscaped, with all that infrastructure underneath, is a problem they’re facing now, and how it can be integrated into a dense city neighborhood without seeming a void remains to be seen.

Right now, though, the stars are aligning for the new Glòries. Jean Nouvel’s sparkling, LED-lit, 466-ft pickle, the Torre Agbar, was built here in anticipation of the Gloriès plan. Already it is a favorite with the Barcelonans; they’ve started spontaneously gathering here to mark the New Year. A prominent local architect, Oriel Bohigas, is building an intriguing Museum of Design (DHUB) in the park, while the old industrial area to the south is being transformed into ‘22@’ (say it ‘vint-i-dos-arroba’), the city’s growing IT and arts district. A major shopping center is in place, and plenty of other private investment is lined up waiting for this pesky depression to go away.

Barcelona, the urban compulsive exhibitionist, is at its best with things that are preposterously colossal, over the top, out of scale (and when they say a billion, pencil in three; development here works just like anywhere else). In the past, Barcelona has often found a way to make its follies pay off. Another part of the Cerdá plan, the Plaça de Catalunya, is one of the biggest squares in the world, but you never seem lost in a vacuum there. The odd shape and the edgy 20’s commercial buildings around it make it a visually unforgettable place, and it’s always full of people. Maybe, with a little help from some second man Barcelona will get lucky again.

Alamedas and Ramblas II: the Promise

Can alamedas be adapted for American city centres? Why not turn the asphalt desert of a ridiculously wide American main street into a linear park like Barcelona’s Ramblas? Why indeed—in big cities or small towns, civilizing a too-wide street could be just the tonic a town centre needs. But there are always some complications in translating an element of urban design from one culture to another.

Can alamedas be adapted for American city centres? Why not turn the asphalt desert of a ridiculously wide American main street into a linear park like Barcelona’s Ramblas? Why indeed—in big cities or small towns, civilizing a too-wide street could be just the tonic a town centre needs. But there are always some complications in translating an element of urban design from one culture to another.Alamedas and Ramblas I: the History

photo: Jorbasa

Remember when you were in Spain. Remember how everything urban there was a just a little shinier, a little buzzier, than anything we gringos can manage. The town, in Spain, is your home, as much as your living room is, and Spaniards can be a little showy about their homes. The shop windows are catchier, the architecture more dramatic, the pavements sometimes bordering on the psychedelic. Amidst oceans of cologne, pastries and ice cream, the streets smell divine.

Nature simply isn’t much fun for months of the year in these dry, subtropical climes, and narrow, shady whitewashed alleys are refreshing always. Here, cities can seem like oases in summer, while country picnics are nearly impossible. To create a fitting stage for urban fun, the Spaniards over the centuries have come up with some of the sharpest tricks in the trick-bag of urban design.

There’s the Plaza Mayor, a sort of building turned inside out. Surrounded by arcades and balconies, with plenty of space for cafes, it’s the perfect urban room; the original, in Madrid, was often used for bullfights. The pavement thing may have started with the Moors in al-Andaluz—intricate patterns of black and white river stones to walk on, as you can still see all over Granada. Lisbon (and later Rio) created dazzling, pop-art pavements of black and white waves, to commemorate the terrible Lisbon earthquake and tsunami of 1755. Now it’s usually artificial stone, or durable, glistening tiles in repeating patterns; it still helps make the evening paseo seem like an event.

Gardens. Not every city might have something transcendent like Aranjuez, or the Generalife in Granada, but there will always be a patch of roses and fountains in the moonlight and all that is conducive to romance. But all this is only preface to another great Spanish contribution we mean to introduce right now. The alameda got its start in 16th-century Madrid, when an indecently proud and wealthy monarchy was transforming that city into the capital of a new empire.

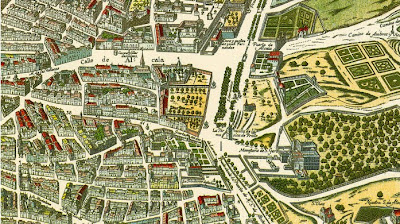

Between the old city and the new Prado palace they were building, Madrid’s designers of the 1570’s added a promenade planted with rows of trees and the city’s first decorative fountains, the Paseo del Prado. Though intended for the king’s triumphal processions, the space under the trees soon became a kind of linear park, while traffic flowed around the edges. (Sadly, if you saw the original Paseo del Prado today, you wouldn’t guess it was ever anything special, because Madrid’s planners could not resist the temptation of making it into part of the main north-south traffic route. The Prado was suffocated by cars, and no one is tempted to linger.)

Of course, in the Catalan parts of Spain an alameda is a rambla, and Barcelona was to build the most celebrated of them all, the ‘most beautiful street in the world’, as García Lorca claimed. A ramla was a torrent or stream in Arabic, and nearly all of the Catalan ramblas cover old streams that had degraded into stinky open sewers—Barcelona’s, where tourists flock today, was once a sardonic joke, called the Cagal.lel, or ‘turd-taker’.

It’s the linear nature of the alameda or rambla that makes it such a delightful urban amenity. You don’t have to come so far for the park; the park comes to you. Some benches and two shady rows of plane trees are all the decoration you require. Since it’s usually one of the main thoroughfares of town, it can take you where you’re going. And if you’re not in a hurry, you can take a seat and watch the people going by. A lot of Barcelonans make a point of taking a stroll on the Ramblas every day, and in summer they secretly wish that all the tourists would go away so they could have it to themselves. They’re so fond of it, it may be the only street in the world that’s been turned into a verb: to do the Ramblas, in Catalan, is to ramblejar.

Free Voina!

The ‘Bulgarian Banksy’ strikes

photo from SophiainBulgaria blog

From left to right: The Mask, The Joker, The Wolverine (who’s he?), Santa, Superman, Ronald McDonald, Captain America, Robin and Wonder Woman. The graffiti underneath says: ‘In step with the times’ (you can see more here).

Almost immediately, Bulgarian and international artists ginned up a campaign to preserve the new paint job, but that wasn’t very likely to happen. The Russian bear never growls louder than when one of its Stalin- or Khrushchev-era war memorials is attacked, which in the former lands of the Warsaw Pact is about once ever fifteen minutes. Plenty of people in those countries still remember what life was like in the decades after their ‘liberation’ from the Nazis. City officials often dismantle them or hide them away in playgrounds in gypsy neighborhoods whenever they can get away with it; younger folk use them for perfecting their spray-paint technique. The big city centre ones, like Sofia’s, have usually been sacrosanct. Nobody wants to poke a bear.

Officials vowed the perp would have to clean the monument personally, but even as they spoke government crews under the lash were hurriedly blasting off all the paint. They made a hash of it, at last report there are still orange and bluish splotches all over the thing. The artist remains at large.